From the “groovy” vinyl boots of the 1960’s, to today’s “stone-washed” jeans, chlorine chemistry has a long-standing role in helping us dress in comfort and style.

Fashion Chemistry

From the “groovy” vinyl boots of the 1960’s, to today’s cool, low-rise jeans, chlorine chemistry has a long-standing role in helping us dress in comfort and style. Chemistry in clothes, you say? Absolutely. For decades, chlorine chemistry has been essential to making clothes more affordable, versatile, comfortable and creative.

Cotton—Comfort Clothing

From favorite T-shirts, to hoodies and jeans, most young people’s wardrobes are full of cotton and cotton-blended clothing. Cotton is an organic fiber that is obtained from the cotton plant. For at least the past 6,000 years, the soft fiber surrounding the seed of the cotton plant has been gathered, spun into thread and woven into soft, “breathable” cotton cloth.

Chlorine chemistry helps boost the cotton harvest by providing chemical compounds that protect cotton plants from insect pests, such as the bollworm, pictured in the photo at left. By reducing insect damage, chlorine chemistry helps increase crop yields, resulting in lower costs for growers and consumers.

Several compounds in the family of insecticides known as the pyrethroids are made with chlorine chemistry. The pyrethroids are modeled after pyrethrin, a natural insecticide produced in the chrysanthemum flower. Pyrethroids are designed to be effective for several months, unlike pyrethrin’s short one-to-two-day window of effectiveness.

Pyrethroids are some of the most widely used, environmentally friendly and cost-effective products applied to cotton plants to protect against the destructive attack of insects. Esfenvalerate is one of the chlorine-containing pyrethroid insecticides. Its chemical structure is pictured below.

Nylon—Debut of a Silk Substitute

Technology imitated the silkworm when nylon was invented over seventy years ago by Dr. Wallace Carothers of DuPont. Chemists had been trying for years to develop a less expensive, synthetic version of the fine, strong thread that is spun naturally by silkworms, and then woven by workers into silk.

Carothers experimented with substances which, on the atomic level, resemble long strands of spaghetti. In 1935 he created one of these megamolecules of the right combination of strength, resilience and potential to be drawn into long fibers—a silk thread substitute. Nylon, the fabric made by weaving together Carothers’ synthetic threads, was the world’s first synthetic fabric. The chlorine-containing compound dichlorobutene can be used in the production of nylon.

One of the first uses of nylon, affordable women’s stockings, became “all the rage” after they were introduced at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Nylon remains a popular, easy-care fabric for all types of clothing, particularly jackets, sports outfits and work-out clothes.

Vinyl on Parade

During the 1960s, the fashion world was busy defining a new look that would reflect the accelerating cultural and technological changes of the post-World War II era. Old rules for hemlines and hair length were “out,” and bright colors and patterns were “in.” Ready-to-wear and easy-care fabrics were a must.

During the 1960s, the fashion world was busy defining a new look that would reflect the accelerating cultural and technological changes of the post-World War II era. Old rules for hemlines and hair length were “out,” and bright colors and patterns were “in.” Ready-to-wear and easy-care fabrics were a must.

In 1966, fashion designer Paco Rabanne issued a challenge to “…anyone to design a hat, coat or dress that hasn’t been done before…The only new frontier left in fashion is the finding of new materials.”

At least one fashion designer, Mary Quant of London, answered the challenge with a line of polyvinyl chloride, or “vinyl” clothing and accessories. A product of many important uses, PVC had never been used for clothing. Suddenly, shiny, vibrant raincoats, boots, purses and wipe-down dresses appeared on fashion show runways. Talk about easy-care clothing! Vinyl, a product of petroleum and chlorine, helped define the 1960’s look. Even today, translucent vinyl handbags make stylish fashion accessories.

PVC Chemistry

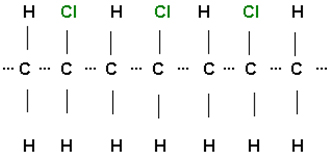

On a molecular level, PVC resembles a stack of untied pasta necklaces. Perhaps you assembled a pasta necklace in kindergarten by stringing pieces of dry pasta on a length of yarn and then tying the yarn ends together. With that fond memory in mind, we can develop a bit of chemical vocabulary: polymers are large, long molecules (pasta necklace) consisting of many smaller chemical units, called monomers (individual pieces of pasta), chemically bonded together. Vinyl and nylon are examples of synthetic polymers; silk and cotton are natural polymers.

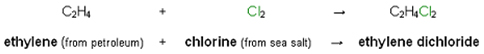

The starting materials for manufacturing PVC are two very common chemical building blocks, ethylene and chlorine. Both of these substances are used to manufacture thousands of items of everyday use. Ethylene, composed of carbon (C) and hydrogen (H) is obtained from petroleum, and chlorine (Cl2) is obtained from salt mines, which are ancient sea salt deposits.

PVC Production

First, the starting materials are combined chemically to form ethylene dichloride.

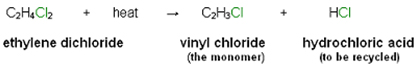

Next, ethylene dichloride is “cracked.” “Crack” is chemical slang—it indicates that the molecule is heated and chemically changed into two new products.

Finally, the polymer is formed by chemically combining the monomers. Note that in the structural representation below, the presence of the vinyl chloride monomer, C2H3Cl, is evident from the ratios of the elements present. For every two carbon atoms, there are three connected hydrogen atoms and one chlorine atom. Thousands of monomers may be combined to form a single polymer of PVC.

Once formulated, PVC is hard and brittle, but it can be made flexible with the addition of plasticizers, and colorful by the addition of colorants.