#CleanWater: Brought to You by Chemistry

ACC celebrates #WorldWaterDay and the White House Water Summit by releasing a video highlighting the many ways chemistry keeps water flowing—from source to tap.

Q: Why is chlorine added to drinking water?

A: Chlorine destroys disease-causing germs and helps make water safe to drink. Waterborne diseases once killed thousands of U.S. residents every year. Following its first use in Jersey City, New Jersey in 1908, drinking water chlorination spread rapidly throughout the United States, and helped to virtually eliminate waterborne diseases like cholera and

typhoid fever.

Drinking water chlorination played a major role in increasing Americans’ life expectancy by 50 percent during the 20th century. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention calls drinking water chlorination “one of the most significant public health advances in U.S. history.”

Besides killing dangerous germs like bacteria, viruses and parasites, chlorine helps reduce disagreeable tastes and odors in water. Chlorine also helps eliminate slime bacteria, molds and algae that commonly grow in water supply reservoirs, on the walls of water mains and in storage tanks. In fact, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency requires treated tap water to contain a detectable level of chlorine to help protect against germs all the way to consumers’ taps.

Q: How is chlorine added to drinking water?

A: Water treatment operators may chlorinate drinking water using either chlorine gas, liquid sodium hypochlorite solution (bleach) or dry calcium hypochlorite. Each of these disinfectants unleashes the power of chlorine chemistry to destroy disease-causing germs in water.

Q: How long has U.S. drinking water been chlorinated?

A: Chlorine has helped provide safe drinking water in the United States for more than 100 years.

Beginning on September 26, 1908, Jersey City, New Jersey became the first U.S. city to routinely chlorinate municipal drinking water supplies. Over the next decade, more than a thousand U.S. cities adopted chlorination, helping to dramatically reduce infectious disease. Learn more…

Q: How common is chlorine disinfection of drinking water?

A: Chlorine is by far the most commonly used drinking water disinfectant in all regions of the world. Today, about 98 percent of U.S. water treatment systems use some type of chlorine disinfection process to help provide safe drinking water. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency requires treated tap water to contain a detectable level of chlorine to protect against germs as it flows from the treatment plant to consumers’ taps.

Q: How does chlorine destroy germs in drinking water?

A: Chlorine destroys waterborne germs by penetrating their slime coatings, cell walls and resistant shells. Chlorine either kills the germs or renders them incapable of reproducing.

Q: How effective is chlorine against germs?

A: Chlorine is highly effective against most disease-causing germs found in drinking water sources.

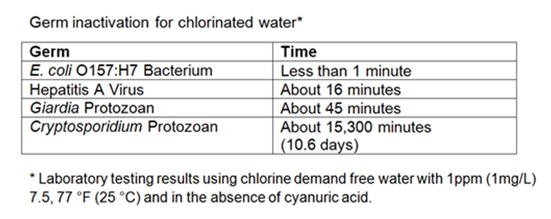

The ability of chlorine to kill germs depends on both the concentration of chlorine in the water and the amount of time that the chlorine has to react with microorganisms (contact time). While chlorine quickly kills most waterborne germs, a few microorganisms, such as Cryptosporidium, are resistant to typical chlorination practices. Therefore, some water systems may require additional treatment steps to protect against particularly resistant pathogens.

Q: Is chlorine in drinking water safe?

A: The small amount of chlorine added to disinfect drinking water in accordance with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations is safe for consumption. According to EPA, allowable chlorine levels in drinking water (up to 4 parts per million) pose “no known or expected health risk [including] an adequate margin of safety” while providing for “control of pathogens under a variety of conditions.”

Q: What are disinfection byproducts?

A: Disinfection byproducts, or DBPs, are chemical compounds formed unintentionally when chlorine or other disinfectants react with natural organic matter in water.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has established science-based regulations limiting certain DBPs (particularly two groups of chemicals known as trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids) in drinking water. These standards have been endorsed by a broad range of organizations, including public health agencies, environmental groups and drinking water utilities. Most water systems meet EPA standards by controlling the amount of natural organic matter present in water prior to disinfection.

While DBPs should be reduced where possible, protection from germs remains the top priority. The World Health Organization strongly cautions that “The risk of illness and death resulting from exposure to pathogens in drinking water is very much greater than the risks from disinfectants and DBPs…Efficient disinfection must never be compromised.”